There is something quietly telling about fashion’s recurring need to borrow shock from pornography. Anyone who has taken a basic marketing course knows the old mantra: sex sells. What is mentioned less often is the second part of that lesson: sex is usually deployed when there is little else left to say. In luxury fashion, the persistence of pornographic references feels less like provocation and more like creative fatigue. What once claimed to shock the bourgeoisie has, over time, become profoundly bourgeois itself. The Porn and Fashion duo is predictable, safe, and almost nostalgic.

JW Anderson’s “PORN” Moment and the Illusion of Transgression

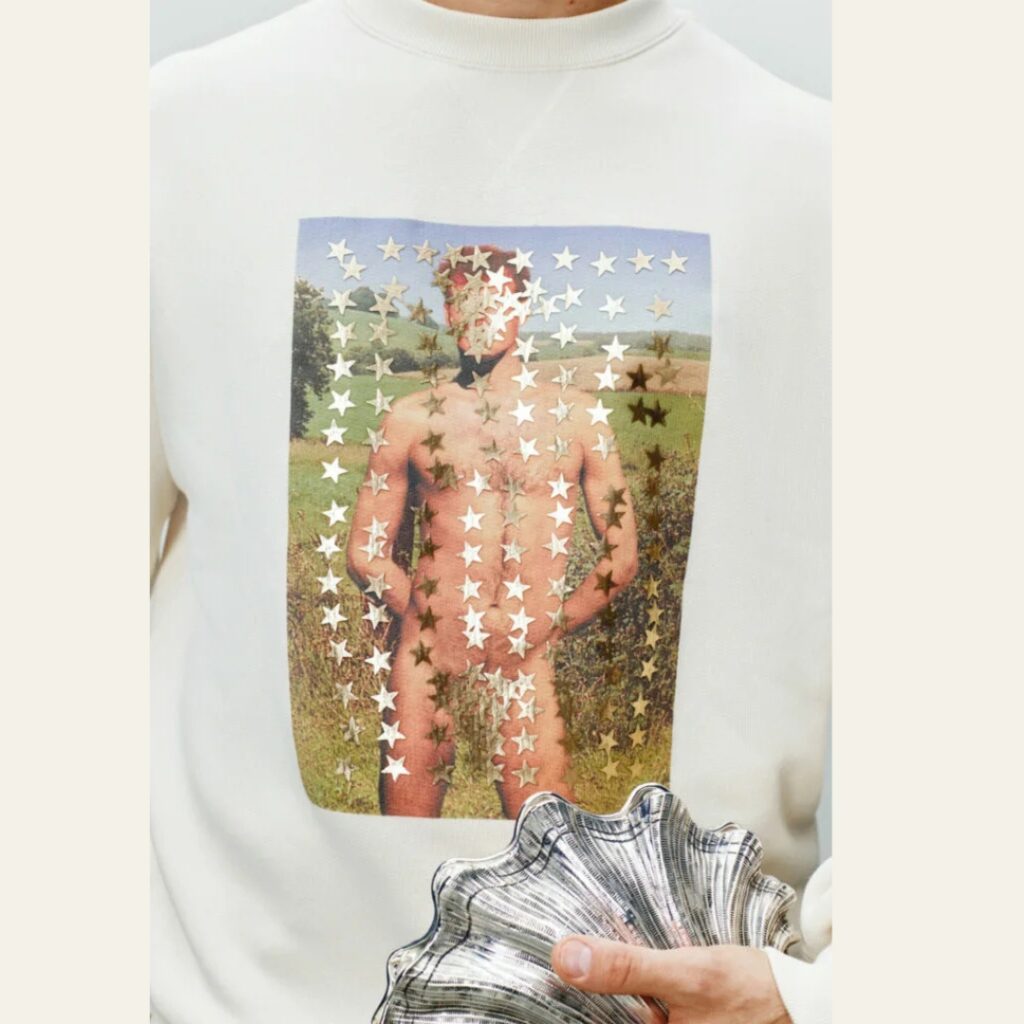

When JW Anderson, newly appointed Creative Director of Dior, presented his Fall 2026 collection, the pièce de résistance was not a silhouette or a fabric innovation, but a T-shirt and tote bag emblazoned with the word PORN in capital letters.

The gesture was framed as irony. As commentary. As clever distance.

@JW Anderson FW2026

But pornography is no longer subversive language. It is mainstream infrastructure. It lives in algorithms, not underground clubs. Its effects are neither abstract nor harmless.

Multiple large-scale studies over the past decade (including longitudinal research published in JAMA Psychiatry and The Journal of Sex Research) show consistent correlations between habitual pornography consumption and increased rates of anxiety, depression, distorted body image, sexual dissatisfaction, and relational disengagement in both young men and women. Among adolescents, early exposure has been linked to higher acceptance of aggression in sexual contexts and diminished capacity for emotional intimacy.

In this context, printing PORN on cotton does not interrogate power. It aestheticises harm.

Who Started the Pornification of Fashion?

To understand how pornography became fashion shorthand, we need to return to the 1990s.

Before becoming the legendary editor-in-chief of Vogue Paris, Carine Roitfeld worked as a freelance stylist and consultant. Her most influential collaboration was with Tom Ford, then Creative Director of Gucci, alongside photographer Mario Testino.

Together, they crystallised what became known as Porn Chic: glossy, hypersexualised imagery that blurred seduction with domination. Later, photographers like Terry Richardson pushed this aesthetic further, producing images that frequently depicted women in submissive poses, simulated coercion, and deliberately infantilised eroticism.

The industry rewarded this visual language. It sold magazines. It sold clothes. It propelled careers. Roitfeld would lead Vogue Paris for fifteen years. Pornography, repackaged as fashion audacity, became an accepted visual grammar.

From there, the aesthetic migrated seamlessly into pop culture, characterised by latex dresses, exaggerated curves, surgical femininity, and ultimately, the hyper-visible family empire of the Kardashians. For over three decades, porn-coded femininity has been marketed not as fantasy, but as aspiration.

When the Industry Knows Better — and Continues Anyway

What makes fashion’s continued reliance on pornographic narratives particularly uncomfortable is that the consequences are no longer hypothetical.

Both Richardson and Testino were later publicly accused by multiple women of sexual misconduct, leading to their effective ban from major fashion platforms. Their work, once celebrated as boundary-pushing, is now widely acknowledged as symptomatic of a system that normalised abuse under the banner of creativity.

Yet the visual language they helped popularise remains remarkably intact.

The industry distanced itself from the men, but not from the worldview.

Porn Is Not Cool. It Is Tragic.

Perhaps the real question isn’t why fashion flirts with pornography, but why it refuses to outgrow it.

The global porn industry is built on female economic vulnerability, coercive labour practices, and a consumption model that rewards extremity over consent. Numerous reports by organisations such as the UK’s NSPCC and the European Institute for Gender Equality document how pornographic norms increasingly shape expectations within real relationships: reduced empathy, performance-driven intimacy, and a growing inability to tolerate emotional reciprocity.

For women, the cost is double. They are asked to consume imagery that erodes their own dignity, then mirror it in their bodies, their faces, their behaviour.

Fashion, at its best, offers women a language of self-possession. At its worst, it becomes a megaphone for cultural habits that quietly dismantle it.

The Emperor Has No Clothes

This is not a call for prudishness. It is a call for intelligence.

In a moment when fashion speaks endlessly about empowerment, sustainability, and care, its continued dependence on pornographic shorthand feels intellectually lazy and ethically thin. True provocation today would not be another slogan designed to generate outrage clicks. It would be a restraint. Maturity. A willingness to imagine desire without degradation.

The king, as the saying goes, is naked. And we have seen enough.

Fashion can do better. The question is whether it still wants to.

FAQ

| Q1: Why does porn keep appearing in fashion? | A: Because it has long been used as a shortcut to attention. Pornographic references promise instant visibility when creative ideas feel exhausted. What once passed as rebellion has become a familiar, low-risk formula. |

| Q2: Is pornography in fashion still provocative? | A: No. Pornography is now mainstream and culturally normalised. When fashion uses it today, it rarely challenges norms. Instead, it repeats a visual language that has lost its power to surprise or question. |

| Q3: What does “pornification of fashion” mean? | A: It refers to the integration of porn-coded imagery into fashion: hyper-sexualised bodies, submissive poses, eroticised youthfulness, and the blurring of desire with domination, presented as style or empowerment. |

| Q4: Why is this problematic today? | A: Because the social and psychological effects of pornography are well-documented. Research links widespread consumption to distorted intimacy, reduced empathy, relational dissatisfaction, and increased anxiety. Fashion’s use of this imagery aestheticises those harms. |

| Q5: Is this critique anti-sex or anti-freedom of expression? | A: No. It is a critique of creative laziness, not sexuality. Sensuality can be expressed with nuance and dignity. True provocation today may lie in restraint, emotional intelligence, and imagination rather than shock. |

Feature Image: JW Anderson A/W 26 (Image: Provided)